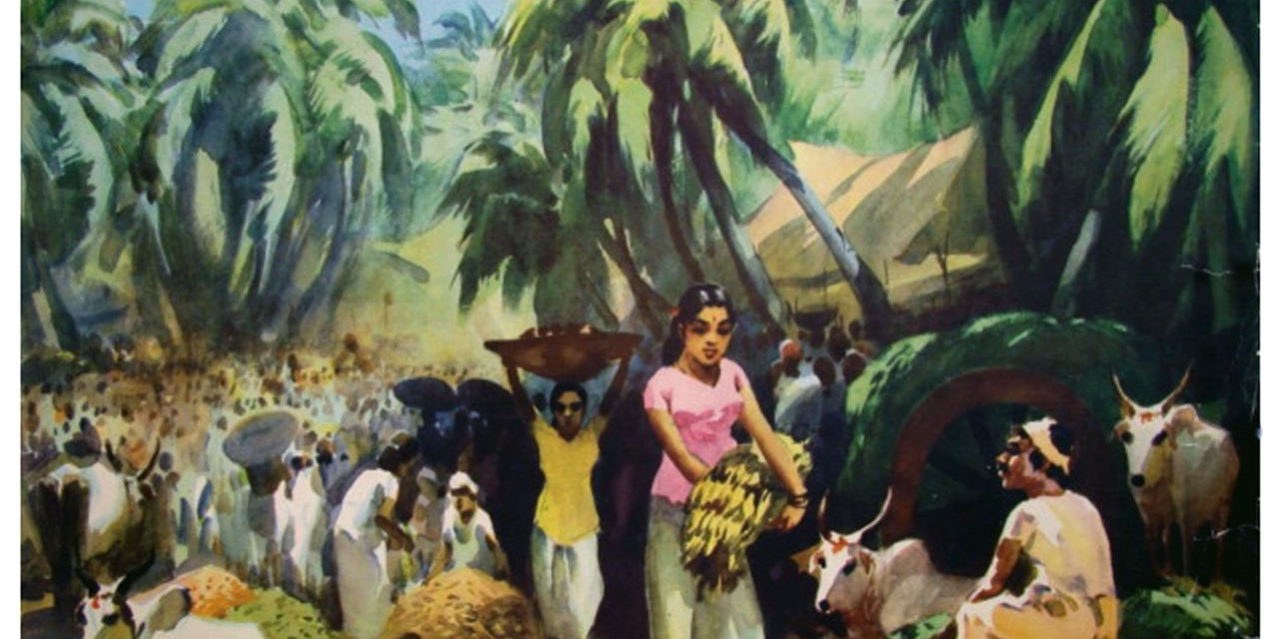

As a child growing up in a village in Kerala in 1980’s with grandparents who were passionate farmers, there was always a lot happening in the backyard. You woke up to the sound of grandmother milking the cows; in harvesting season the entire village came together to work as one. The coconut harvesters were a favourite, shooting into the skies effortlessly. And the food that came from our backyard was delicious and wholesome, be it the brown rice, the eggs and thick milk that came from each household farm, the beans, spinach, drumsticks and the array of tubers that were home-grown. Each household had its own orchard of mango, guava, cherry apples and mulberry. My happiest childhood memories were helping my grandparents tend to their farm, watering the plants, helping graze the cows, playing with the dog, and climbing the many trees.

The village was a community knit together by the common thread of working the land together. Pests, irrigation, fertilizers, labour issues and harvesting issues if any were churned out together.

Agriculture broke barriers of caste, religion and culture. My Christian grandmother worked side by side with Muslim and Hindu workers in paddy fields for years, as one family. The familial ties were much stronger as the father, mother and children all tended to the same interest.

When the GYOF initiative started, I tried to recreate this experience for my children, and we invested in a small kitchen garden at first. Setting up a backyard garden in one of the most urbane areas of Kochi was a revelation. My aged in-laws, my spouse, our three kids and our maid fell in love with the vegetable garden. The dining room conversation was suddenly about farming techniques. In fact, the entire community around our house replicated our garden and there were smaller versions on terraces, balconies and tiny courtyards. My neighbourhood womenfolk gathered around the garden with suggestions and enquiries.

In order to improve the yield from the garden and to counter our heavy rainy season, we decided to invest in a poly house – and that was another revelation!

As techies, we had no formal training in setting up a poly house unit. The poly house contractor set up the poly house without considering pre-requisites of sunlight, direction and area. We struggled with finding the right seedlings suited for the poly house. (In spite of attending a lot of training programmes we were still not sure about the right potting mix).

The quantity and periodicity of Fertilizers to be applied was also vague. Coming back after a day’s work sometimes we even forgot to water the plants.

Pests, both seen and unseen lurked in the poly house and the online research fell flat in this area.

In the midst of all this learning, we realised that most of our friends who had also dabbled in farming had given up due to the same challenges. And that’s how we learned the hard way that amateur farming without proper guidance almost always leads to failure, that failure increases our dependence on pesticide-rich vegetables which in turn is linked to the rising incidence of cancer. Also, the lack of accessibility to fresh vegetables meant denying our young generation the right nutrition. So that made us even more determined to make GYOF a community-centric initiative.

A whole lot of learning.

To me, it was important to revive our respect for the soil, start taking pride in our land and set a good example for the future generation. But we had to first to educate ourselves.

We had to learn the correct way to construct Poly houses so that just the right amount of sunlight enters it and the temperature inside is made optimal.

We had to learn to how to manage the mundane tasks of fertigation, irrigation and pest control preventives so that it becomes a sustainable model that would suit our busy lifestyles.

Once we got the Poly house under control, we had another challenge to deal with: Waste management. The general public has very little awareness of best practices of waste management, with both wet and dry waste dumped together which attracts flies, mosquitoes, stray dogs and rodents. Add to this the onslaught of the monsoons and a whole spectrum of fevers sprout up in our land. We realised that just the basic act of segregating food waste and plastic waste and composting food waste to get a fertilizer for a kitchen garden allowed us to bring in conservation into our homes.

Still learning, still growing…

We have a long way to go still but it has been an amazing ride so far. Our backgrounds and experience taught us that automation can transform unorganised sectors like construction, and raise control and productivity, so it made sense to apply that to the GYOF programme also and that is what we tried to do – we tried to transform backyard farming with technology.

As I look back on the GYOF story so far, two quotes come to mind:

Albert Einstein said, “The world is a dangerous place to live; not because of the people who are evil but because of the people who don’t do anything about it.”

And, “Eat your food like your medicine else you will end up eating medicine like food”, Ratan Tata.

I couldn’t agree more!

Maya Varghese

–